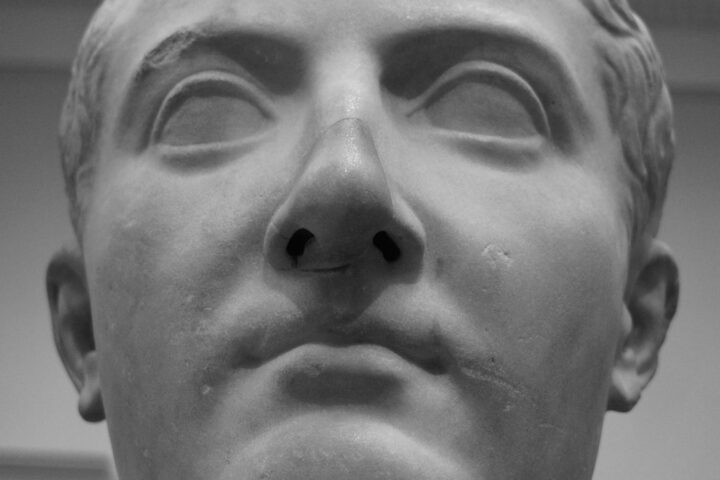

Gaius Sulpicius Galba, who reigned as Roman Emperor from June 68 to January 69 AD, is often castigated by historians as one of Rome’s least effective and most reviled leaders. This condemnation primarily stems from his rigid and authoritarian governance, his disregard for the well-being of the Roman populace, and his inability to secure military loyalty.

Upon seizing power through a revolt against the increasingly despotic Nero, Galba initially appeared as a beacon of hope. However, his tenure as emperor swiftly descended into chaos and discontent. His leadership style was marked by an inflexible austerity that alienated both the Senate and the common people. Galba’s failure to reward the soldiers who had brought him to power, coupled with his refusal to disburse customary donations to the Praetorian Guard, sowed the seeds of disloyalty among the military ranks. This unforgivable oversight, in a society where loyalty was often secured through financial and ceremonial gratifications, severely weakened his support base.

Moreover, Galba’s attempt to combat Nero’s financial excesses by enforcing stringent economic reforms only deepened public resentment. His measures, such as the rigorous collection of taxes and the seizing of estates from Nero’s favoritism, although fiscally prudent, were perceived as draconian and precipitated widespread disenchantment.

Galba’s most significant misstep, perhaps, was his exceedingly poor judgment in appointing Lucius Calpurnius Piso Licinianus, a relatively obscure aristocrat, as his successor. This decision angered Otho, a prominent supporter who had expected to be named heir. Feeling betrayed and sidelined, Otho orchestrated a coup with the support of the disaffected Praetorian Guard. On January 15, 69 AD, Galba was assassinated in the Roman Forum, a grim end to a short and tumultuous reign, marking a year that would be remembered as the “Year of the Four Emperors.”

He’s downfall can be attributed to his unyielding and austere policies, his neglect of the essential support systems of the Roman political and military apparatus, and his inability to cultivate loyalty among key factions. His short-lived rule is a somber testament to the perils of rigid adherence to principle in the harsh, pragmatic world of Roman imperial politics.